Previous notes:

When you’re building a multi-tenant system, you need guardrails. Without quotas and limits the product becomes the wild west: one user eats up everyone’s resources, and the rest of your users suffer.

You know that old saying, “You can’t have too much of a good thing”? I intend to make Runbook the “good thing” for workflow orchestration. But even good things need boundaries. This week, I tackled runtime quotas and concurrency limits.

Runtime Quotas

What is a “Runtime quota”? Glad I asked.

Think of a workflow with some parallel and some sequential steps. Each step runs in isolation, does its thing, and notifies everyone when it’s done. The orchestrator decides whether to run the next step or mark the workflow as finished.

All of this magic happens in a computer, hidden away behind the clouds. But this computer is leased to you for an amount of time… and that time is unfortunately not infinite.

In order to not let people take advantage of the platform, I decided to put some Runtime quotas in place, depending on the pricing plan the user (or their tenant) is on. Quotas are expressed in minutes, similarly to what other CI/CD runners are doing (e.g. Github’s 2000 minutes/month). Tracking these minutes is easy, the hard decision comes what to do when the minutes run out. Say a user has 5 minutes left of their quota, and they start a workflow that happens to run for 10 minutes. There are two possible outcomes:

-

Stop the workflow after 5 minutes. You get what you paid for; there’s no free lunch. This is not impossible to implement, since I already have the infrastructure in place to stop workflows at any time, but imagine being the user. You have a production bug, you just pushed your fix, using Runbook to handle Continuous Integration and Deployment, and 5 minutes later you get a BIG NO-NO from yours truly.

-

Let the workflow finish, and the user owes me 5 minutes of runtime. These can be deducted from the next payment, e.g., instead of starting the next month with 2000 run minutes, they start with 1995 minutes. Easy to implement, helpful for the user since they get their workflow finished as expected.

I obviously decided to go with the latter, after a LinkedIn vote.

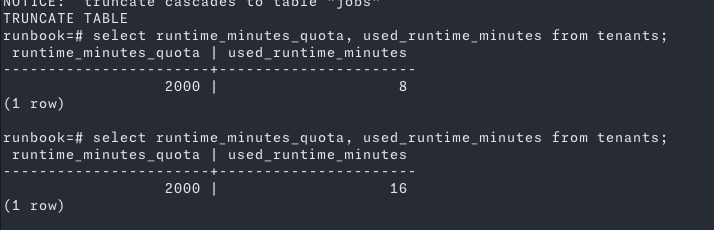

And don’t forget parallelism: two parallel steps running for 5 minutes each = 10 minutes of quota usage. A neat little SQL query solved that:

SELECT SUM(

CEIL(EXTRACT(EPOCH FROM (finished_at - started_at)) / 60)

)::int AS total_duration_minutes

FROM jobs

WHERE workflow_id = 'id';It works like a charm:

Concurrency Limits

Quotas protect how much you run. Concurrency limits protect how often.

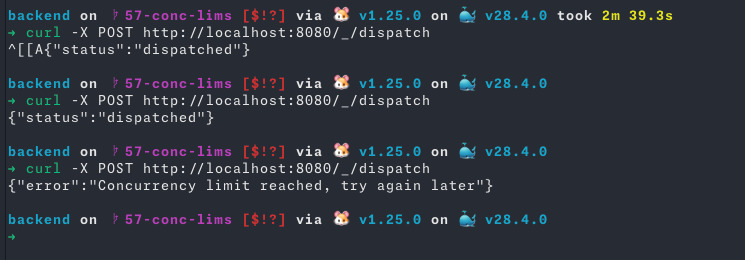

A concurrency limit defines how many workflows a user can run at the same time. It doesn’t limit parallel jobs inside a workflow, only how many workflows you can kick off simultaneously.

For example, a concurrency limit of 2 allows only 2 workflows to run at the same time, while any others must take a ticket and get in line:

This protects the system from users spamming workflows.

Try again later?!

“But I don’t want to try later,” - you might say, - “I want you to try again later!” That’s what computers are for, right? To remember to do things humans forget to do.

If a user ate up all their runtime minutes, it’s fair to not run their workflows until they get some more minutes (e.g. next cycle). But if a user is trying to schedule more workflows than their plan allows them, if they have the minutes to run the workflows, I can’t stop them from doing so. Enter Outbox pattern.

When a workflow can’t be executed due to the concurrency limit reached, the workflow is

marked as Pending Execution. The moment a slot frees up (i.e. when the user

has less running workflows than what their limit is) the system autoschedules the pending

workflows, in a First-In-First-Out manner. In technical terms, this requires two things:

- Ordered Storage: locally order workflows by timestamp, keep in mind any potential partition.

- Relay Service: Either schedule a service to dispatch a workflow into execution, or pick up a “workflow finished” event and react on it

Guess which one I’m doing, and which one is the easiest to do…

Until next time.