The job of an architect is not to make decisions, but to defer decisions as long as possible, to allow the program to be built in the absence of decisions, so that decisions can be made later with the most possible information.

A quote by Uncle Bob Martin. Keep that in mind. It’s the theme.

The Problem Before the Code

About a month ago, a friend asked me how I’d design a scalable workflow system. A thought experiment; we then spent 45 minutes on a call discussing the usual suspect questions:

- How do we ensure workflows run in parallel, and steps run in order?

- How do we scale when there are too many workflows to run?

- How do we track execution state?

- Can the output of one step feed into another?

- How do we handle failures?

A few times in that call, the question “Should we use Kafka or RabbitMQ here?” was asked, and the answer to it was “Irrelevant, let’s first understand and solve the problem”.

Because this isn’t a problem of tools, it is a problem of orchestration. Step coordination, not execution. Until that’s solved, the infrastructure is just noise.

When you think in terms of tools, you inherit their constraints. When you think in terms of concepts, the constraints emerge from the problem itself. That’s how you stay honest. It became clear to us we’d need a queue, but whether it should be RabbitMQ or Kafka was not clear yet. And that’s fine. That decision could wait.

First Steps with Runbook

Two weeks ago, almost 40°C outside, I decided to keep myself entertained with writing the workflow orchestrator from that one call I mentioned above. We’ll call it Runbook (name subject to change).

I had minimal requirements in mind:

- Workflows are linear, simple chains of steps, defined in YAML

- Each step runs Bash commands or scripts

- Workflows run independently in parallel

- Steps execute sequentially

- If a step fails, the workflow fails

- The YAML can change mid-execution, but shouldn’t affect already-started workflows

This is very different from the end goal: a workflow runner comparable to Github Actions, Circle CI, and what have you. But these requirements are intentionally limited: minimal constraints lead to minimum viable programs. I didn’t want to spend time thinking about how users create workflows, where/how they are stored, how logs are displayed. I didn’t even want to think about users at this point. Those decisions can wait.

All I was working with was:

- The system should react to events like

workflow_started,step_failed, etc. - The system must be highly concurrent. Whether that means OS threads, processes, or VMs… 🤷♂️ Who cares.

So I made two early choices: Kafka and Go.

Why Kafka?

Familiarity. And simplicity.

They say it’s world class for event streaming, and I’ve always been known to trust the hype 😉

My workflows are keyed, and I can use that as a partition key in Kafka. Knowing how consumer groups handle partitions lets me design my workers to be long-lived and stateful. Keeping that state in memory simplifies my initial infrastructure a lot and enables fast iterations, at the price of having to rebuild state when a new worker is spawned, but that’s a very small price for now. This decision really paid off last week, when I decided to switch from linear workflows to graph workflows, which required rewriting almost all of the workflow orchestration logic.

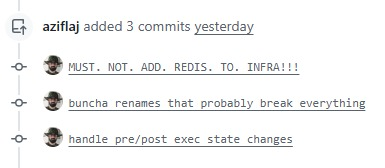

Speaking of keeping things simple, I was this close 🤏 to adding Redis for state management when supporting these graph workflows. Using Redis sets and Redlock would make state handling easier, especially if when the system goes online and real users start piling in. But I’m not sure it’s the right solution. I’ll eventually need a database anyway, especially if I want to have users in my platform, and whatever database I end up using will likely have a similar mechanism for state management and I won’t really need Redis. So I’m deferring Redis, and I’m deferring the database decision. Those decisions can wait. For now, in-memory state management will do.

Why Go?

Familiarity. And simplicity. Deja vu.

Workflows need to run concurrently. Whether I decide to eventually spawn OS threads or Kubernetes pods to run workflows, it currently doesn’t matter. For now, I need to:

- Spawn the right thing when a step starts

- Wait for it to complete

- Stream its output somewhere (

$stdout? file? ELK stack? 🤷♂️ dunno) - Handle

SIGKILL/SIGTERM/SIGINTgracefully

All these come easy to me with goroutines, WaitGroups and channels (obviously simplified version of what I had until a week ago):

func (w *Worker) Run(ctx context.Context) {

// ... code omitted

// Worker pool to Spawn the right thing when a step starts

for i := 0; i < w.poolSize; i++ {

go func() {

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case job := <-w.JobCh:

w.OutCh <- w.processJob(ctx, job) // Wait for thing to complete

}

}

}()

}

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return // Handle signals gracefully

case out := <-w.OutCh: // Stream thing's output somewhere

fmt.Println("output: ", out)

}

}

}Is Go the best choice? Generally speaking? In the long term? Probably not, probably Erlang or Elixir would be best, mainly because of how BEAM can orchestrate clusters of machines. But I know Go better than Elixir. That does it for now.

From Toy to Tool

Now I have a working toy: a Workflow Orchestrator that runs Bash scripts in the least secure way. But it works, as far as prototypes go. And now, more decisions loom:

- How do I store and consume workflow definitions?

- Do I want to move from stateful workers into a stateless model?

- How do I expose step results for real-time and historical views?

- How should errors bubble up to users?

- What kind of database can handle high-throughput, append-only log data?

- Should steps be allowed to retry? Be skipped? Be paused?

Some of these decisions can still wait. But the system is malleable, and that’s the whole point: I build by not rushing the decision that doesn’t need rushing.