Yesterday I did a presentation titled “The No Bullshit Guide into Building Software”, as a way to share my experience in the industry regarding what I’ve seen is a good approach when building, or helping engineers build better software. This blogpost is created by reusing the notes I wrote before the presentation, and what was said during the event doesn’t go far away from what is written here. You can find the slides here

I’m assuming all of us here are doing something towards building, or helping to build, software. We’re all at different stages of our career and we all have different approaches to doing our work, which also implies we mean different things by bullshit. Some of us consider bullshit what we don’t know or understand, and some others think that anything done differently from their approach is bullshit. And that’s one of the side effects of seniority and experience, having opinions. The opinions formed during the years of experience are one of the main differences between a senior and a junior practicioner in the software industry.

I have been meddling with code since I was underaged, and in these 10+ years of having to stare at a computer screen for hours every day, I’ve come to the realisation that during these 60 years that Software Engineering has been existing as a practice, the front end people only recently have had the chance to work with really interesting and complex stuff. Before, the frontend would just render whatever the server replied with, maybe do some jQuery shenanigans to make things look better, but that was it. Nowadays you get SPAs, PWAs, micro-frontends, all these ES6/7/8/9/whatever the latest number is, build pipelines and much more. Given the massive number of people that are joining the industry as frontend developers, along with the lack of experience and that of the maturity of the front-end as an engineering practice, the No-Bullshit Guide into Building Software could be summarised as…

Welcome to my TED Talk, are there any questions?

Disclaimer towards JS developers: I don’t believe all of you are complete numbnuts, but it’s fun having a go at your community.

So who am I? Yada yada yada, I work for a Finnish scale-up called Leadfeeder, and before that I worked in this other local start-up called Publer that almost all of you have heard before. All that I’m sharing with you today are opinions backed by my experience, and in no way are the absolute truth. If you disagree with me I’m very open to discussion, maybe one of us ends up changing their mind.

Before moving ahead, it’s better to define some terminology. What I mean by bullshit during this presentation, is anything that makes building software harder and longer. Any practice that doesn’t necessarily add value to the software process, is bullshit. Anything that makes you wanna stop doing software, is bullshit. And on the other hand, anything that you love but isn’t needed to the software you’re building works towards clouding your judgement, so is therefore also bullshit.

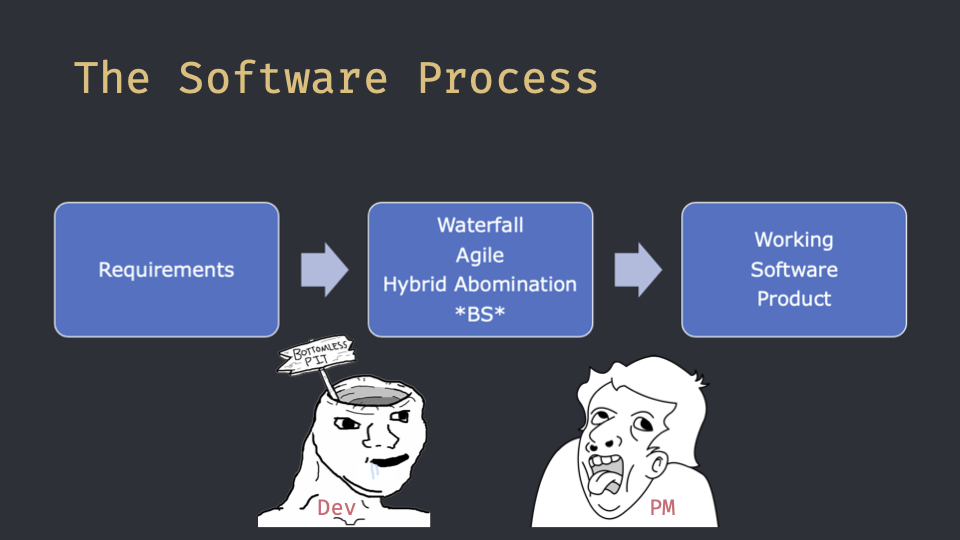

Now you all know, or you’re supposed to know, what the software process is. Either some waterfall (which is cool) or some agile (which is also cool) or even weird mix of different software development processes (again, cool), with the right steps and the right transitions between steps, that converts a list of requirements into a working software product. And there are a lot of actors that contribute their own bullshit to the process, but mostly it’s Project Managers, Product Owners, or Product People in general; and Developers, or Engineers, or maybe Code Monkeys when they start acting like prima donnas.

And usually, the bullshit these two actors introduce into the process always affects the other actor. And what’s something all Product People love and all (well, most of) the Devs hate?

Meetings. Geez, PMs want to have a call for everything. They want to have a call for this and a call for that, and they want to have another call to schedule those other calls, but then again whatever time you propose for them is not going to work because, well, they have another call at that time.

What I see as a mistake in some of the Product People I’ve worked with is an issue with how they regard Agile methodologies in general. They seem to forget the “People over Processes” thing, and focus too much on the process instead. So we get

- Sprint planning & estimation calls…

- Daily stand-ups to inform Product People on the progress

- Every 2 weeks (or however long the Sprint is), we get Reviews and Retros

- And there’s all the ad-hoc calls you get invited at, because the Product people don’t know what to tell to the stakeholders, so they add a developer on the call.

Context switching is costly for developers. Along with the preparation before the call, as well as the effort to get back to writing code after the call, a 30-minute call for a developer could translate into 1 hour spent on not building that feature every Product Person wants built yesterday. Devs don’t need to have daily stand-ups because most of the time, they work together. They already know what other developers on their team are working on; they review their Pull Requests. And estimations are never right.

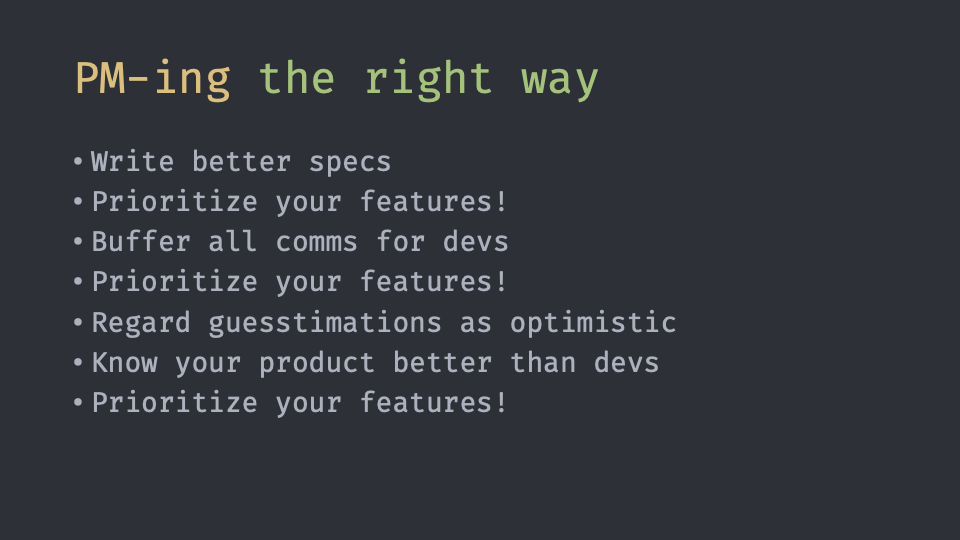

So, for a better PMing experience…

-

Write better specs. Give your developers all the tools they need in order to build what you have in mind. Whether it be mockups, user stories, actual VS expected system behaviour, etc. We will still come at you with questions, but better to make educated questions rather than “So… what do you want me to do about this ticket?”

-

Prioritise your features. By having constant contact with stakeholders and/or the client, the product people can (and should) decide which of the tickets will be done before the others.

-

Make sure to not let people distract your developers. That’s more of a Cache Proxy rather than a Buffer, but you get the idea. Don’t let other employees of the company, and especially not the stakeholders, to go to the developers and ask them about the progress of their features. The product people should be the information point for all non-developers.

-

Prioritise your features! Developers don’t know what the stakeholders need, so most of the time they will prioritise tech-improvements and technically challenging tasks, rather than features the users/clients need

-

Consider all estimations as optimistic, and when passing on deadlines, add a couple of extra days (or even weeks) to make sure everything works fine. Bugs arise all the time, almost always after the deadline and when the application is deployed in production. Having a soft and a hard deadline always helps.

Can you guess what the next one will be?

-

(expect the unexpected, and) Know your product. Just like the developers know the system from a technical point of view, you should be the go-to person for product-specific questions. And always…

-

Prioritise your features. Devs are generally good at prioritising what they like, and even better at pushing away tasks they don’t want to “lose time with”. So one of the things you’ll hear most often from developers is:

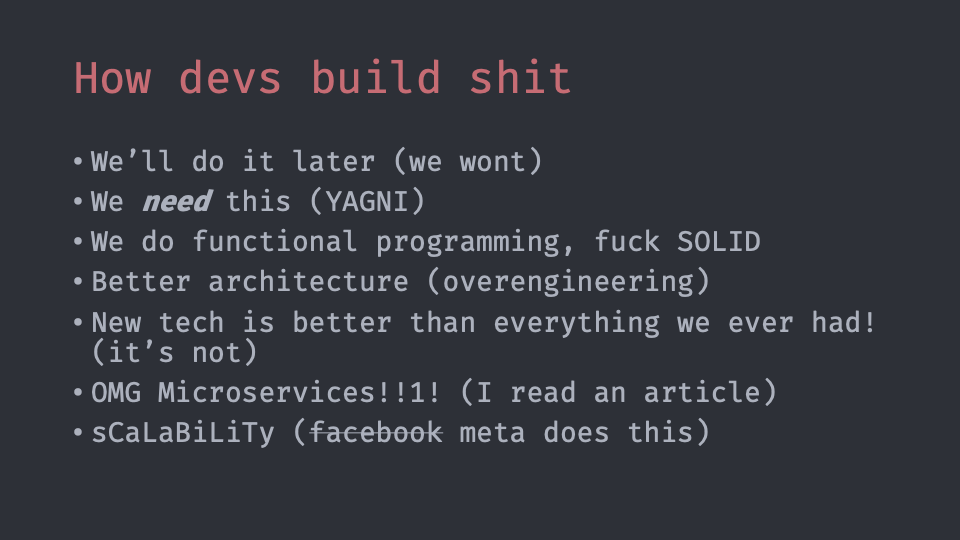

“We’ll do it later”. Surprise surprise, we won’t. This is just one thing we tell you so we don’t “lose time” on “unnecessary shit”. And how we prioritise, especially when it comes to technical solutions that are very good and very much needed (if we do say so ourselves), is by saying “we need this”. Most likely, we won’t ever need it, but we’re trying to see a bigger picture that will never be painted.

And then there’s our technobabble, throwing away years of experience because we’re using a “new” paradigm; or we talk about having a robust architecture which handles everything the rightest and bestest way possible (and most likely it’s overengineering of a very simple use-case); or we talk about that new technology we learned about in a webinar or a conference that “is just better at everything than whatever we’re using right now” (…it’s not)

Most of these are just solutions for made up issues we think we will have, and we try to fix these issues in the only way we know… that one way described in that article we discovered last night on Medium. We follow advice on how big companies handle their issues, without thinking if their solution really applies to our problems. We forget that the field of Software Engineering has existed since the 60s and that in the last 60 years, most of the problems faced by most of the people already have a well-tested approach.

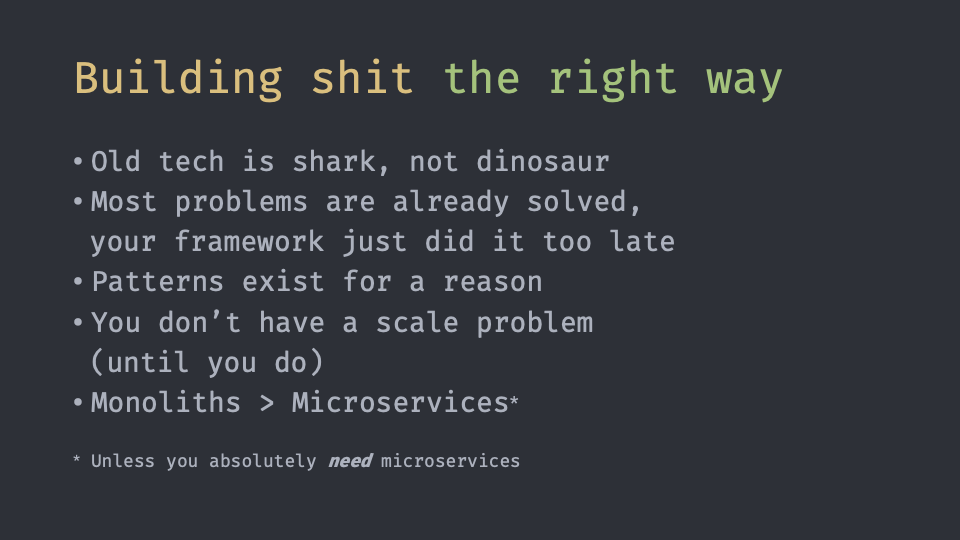

So maybe, the first thing to do is to realise that old tech, that one thing that didn’t really evolve for the past 20 years (or 5 years if you’re a JS developer) is not extinct like dinosaurs. It’s actually well aged, and the reason it’s still alive and still used is a strong indicator of that well-aged-ness (think of the 50-years old Unix and of 15-years old Django versus the very young and almost unused anymore Meteor.js).

History repeats itself when it comes to new technologies, because most problems are already solved in a smart way. Back in the 80s, when HTTP didn’t exist and people were doing distributed computing via RPC, life was good. Then in the 90s, with the massification of Object-Oriented Programming, Calling a Procedure in a Remote computer was rebranded into Invoking a Method in a Remote computer, giving so birth to RMI - the new RPC. Then times evolved, HTTP became a thing and people started using XML to describe which method to invoke into a remote object; we started calling this XML-RPC but the name didn’t stick, so we renamed it to SOAP. And SOAP was good for a while, unless you had to cache some response; so we came up with a better approach: RESTful APIs. Instead of calling a method on a remote object, using REST we call an HTTP Endpoint… which then gets mapped to a function or to a method in an object in the server. The two newest approaches to “solving the problem” of calling a procedure on a remote computer, GraphQL and gRPC, are also reiterations of two older approaches to solving the same problem, respectively SOAP and (surprisingly) RPC. Almost all new tech is just old tech written differently.

When it comes to patterns, rather than ways to put files into folders, it’s better to view them as generic structures that help you approach the solution of analogous problems. Just because you learned most of them in school and practiced them in an OO-language, it doesn’t mean that the same patterns can’t be used in non-OO programming.

And when it comes to scale issues, most of the time they’re inexistent. When I used to interview people, I’d always ask them the same question: “How do I migrate my database and make sure that there are no downtimes due to database locks?” The solution to this can be as easy as “Run the migrations during night-time, when all the users are asleep”, or as complex as having multiple replicas and handling rolling migrations and dealing with replicas with different database schemas for an indecisive amount of time… surprisingly most people never asked me about the scale of the application, they always went with the bestest solution described by the biggest companies out there.

You don’t have a scale problem, until you have a scale problem. And when you do have a scale problem, then the microservices are not the silver bullet. It’s easier to have a monolith and scale it either vertically or horizontally, rather than invest time into splitting a monolith into microservices. Monoliths are better to begin with, faster to develop, easier to deploy, simpler to maintain. When moving a module out of a monolith, you’re changing a function call into a network call, which can fail for more reasons than a plain-ol’ function call. A network call is also slower than a function call, so there goes our performance…

There is nothing wrong with monoliths… until they become enormously unmaintainable. Maybe then it’s better to think of splitting it. But proceed with care. More moving parts means more things that can go wrong, and according to Murphy’s law “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong”