As I said last time (link to Part 1), in this blogpost we’ll continue with the same codebase and we’ll check how Devise manages user authentication. In our case, what we’re doing is a simple email/password login from an HTML form, but it might seem like black magic; the code that actually does the thing, is nowhere to be found…

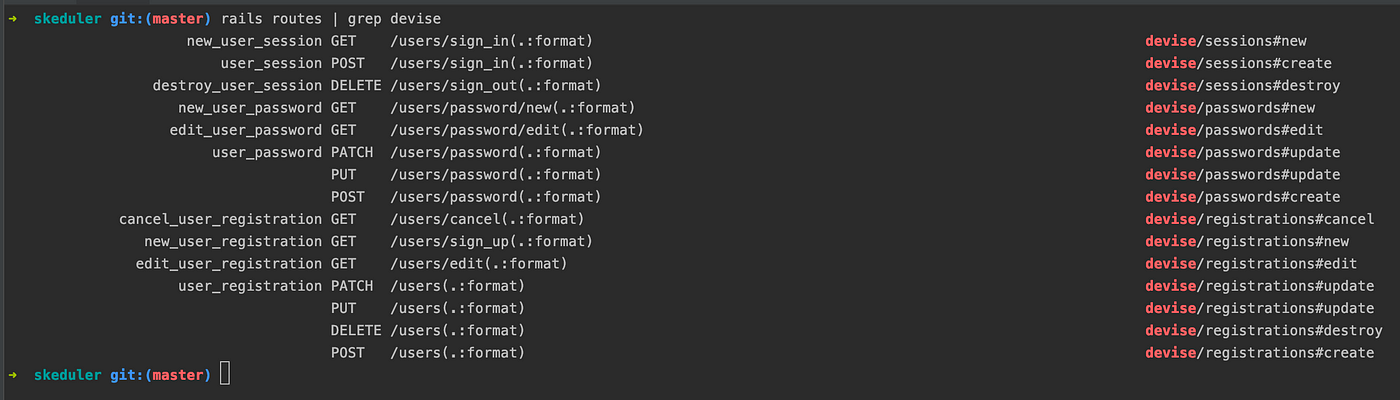

You can see all the endpoints exposed by our application by running rails routes in the terminal. That’d actually be a lot of information, so lets see this instead:

All those endpoints, added by Devise, point to controllers that live inside the gem. If you visit one of those, e.g. http://localhost:3000/users/sign_in, you’ll see a login form. The views exist inside app/views/devise, but the controllers are inside of Devise. The rendered view is nothing but bare bones, pure HTML, with almost no styling. Let’s change that.

Get ClaCSSy

We’ll be using MaterializeCSS for styling the app. There’s a gem available (materialize-sass), so follow those directions to install and set the gem up. Don’t worry if you can’t find an app/assets/javascripts/application.js file in your project; Rails 6 doesn’t ship with an app/assets/javascripts folder, so you can just create it manually. Now, I’m going to update the styles for some of the views without giving much explanation (the only explanation is “I felt like this looks good”), but you can see all the changes here. You might find this syntax unknown:

<%= render 'shared/header' %>This line tells Rails that we want to render a partial, a reusable partial view that does not belong to a controller. In the above case, a file named app/views/shared/_header.html.erb is rendered. Notice the underscore before the filename; that’s how Rails knows this is a partial view.

Now that Materialize is installed and we already have some styles in our app, we’ll start customising Devise’s views. You can find the Sign Up screen at app/views/devise/registrations/new.html.erb and the Log In screen at app/views/devise/sessions/new.html.erb, and my updated styles here. I also updated the password reset views for you.

Get into Devise

As you might’ve noticed by now, Devise handles everything that has to do with user sessions and registrations. It also manages password resets (in case any user forgets their password), email confirmation, social login (through a plugin), etc. So now is the time to create the first account by signing up. After signing up, open up a terminal window and run rails c (c stands for console). In the console, run:

User.first.usernameApparently, our username isn’t stored. And that’s because Devise has no idea what to do with this field. All it knows is that users register with an email and a password, nothing else. So, to permit this new parameter to be stored in the model, we need to let Devise know about it:

class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base

before_action :configure_permitted_parameters, if: :devise_controller?

protected

def configure_permitted_parameters

devise_parameter_sanitizer.permit(:sign_up, keys: [:username])

end

endNow, you can try again, and you’ll see that the username is stored in the database.

Now, we want users to be able to login using either their email, or their username. There are a couple of ways to do this, but we’ll use the official way.

You can check all my changed files here. There are a lot of changes in that commit, but all of them are coming from the docs and they give a good explanation on what everything does. In order to not confuse some emails with usernames (e.g., if some user sets their username to something that looks like email), I added some validations (and spec) to check if the username matches a certain RegExp. I’m not allowing special characters in the username, and they can’t start with a digit (for no real reason besides me not liking the usernames that start with digits).

Don’t forget about Rubocop

Rubocop is a dependency we installed on Part 1, and we didn’t really configure it. So if I run rubocop on terminal, I get 243 offenses. That’s not cool. That’s 243 times I’ve been added to Santa’s naughty list. So, let’s configure Rubocop and see how many “mistakes” I’ve really done.

Rubocop takes his orders from a file called .rubocop.yml. In this file, we’ll list all the rules we want to follow when writing code. Notice that this isn’t a standard way of writing Ruby. The good (and the bad) thing of most programming languages, Ruby included, is that you can write code in any way you want; the machine doesn’t care. But good programmers write code that other programmers understand. So, here’s my .rubocop.yml:

require: rubocop-rails

AllCops:

TargetRubyVersion: 2.6.3

Exclude:

- 'db/**/*'

- 'bin/**/*'

- 'vendor/**/*'

- 'config/**/*'

- 'spec/spec_helper.rb'

- 'spec/rails_helper.rb'

- 'node_modules/**/*'

Rails:

Enabled: true

# Commonly used screens these days easily fit more than 80 characters.

Metrics/LineLength:

Max: 120

Metrics/AbcSize:

Max: 20

# Too short methods lead to extraction of single-use methods, which can make

# the code easier to read (by naming things), but can also clutter the class

Metrics/MethodLength:

Max: 20

# The guiding principle of classes is SRP, SRP can't be accurately measured by LoC

Metrics/ClassLength:

Max: 1500

Metrics/ModuleLength:

Max: 1500

# Messes with my RSpec cases

Metrics/BlockLength:

Max: 500

Style/EmptyMethod:

Enabled: false

# We do not need to support Ruby 1.9, so this is good to use.

Style/SymbolArray:

Enabled: true

# Mixing the styles looks just silly.

Style/HashSyntax:

EnforcedStyle: ruby19_no_mixed_keys

# has_key? and has_value? are far more readable than key? and value?

Style/PreferredHashMethods:

Enabled: false

Style/CollectionMethods:

Enabled: true

PreferredMethods:

# inject seems more common in the community.

reduce: "inject"

# Either allow this style or don't. Marking it as safe with parenthesis

# is silly. Let's try to live without them for now.

Style/ParenthesesAroundCondition:

AllowSafeAssignment: false

Lint/AssignmentInCondition:

AllowSafeAssignment: false

# A specialized exception class will take one or more arguments and construct the message from it.

# So both variants make sense.

Style/RaiseArgs:

Enabled: false

Style/FrozenStringLiteralComment:

Enabled: false

# Indenting the chained dots beneath each other is not supported by this cop,

# see https://github.com/bbatsov/rubocop/issues/1633

Layout/MultilineOperationIndentation:

Enabled: true

# Fail is an alias of raise. Avoid aliases, it's more cognitive load for no gain.

# The argument that fail should be used to abort the program is wrong too,

# there's Kernel#abort for that.

Style/SignalException:

EnforcedStyle: only_raise

Style/RescueStandardError:

EnforcedStyle: implicit

# Suppressing exceptions can be perfectly fine, and be it to avoid to

# explicitly type nil into the rescue since that's what you want to return,

# or suppressing LoadError for optional dependencies

Lint/HandleExceptions:

Enabled: false

# do / end blocks should be used for side effects,

# methods that run a block for side effects and have

# a useful return value are rare, assign the return

# value to a local variable for those cases.

Style/MethodCalledOnDoEndBlock:

Enabled: true

# Enforcing the names of variables? To single letter ones? Just no.

Style/SingleLineBlockParams:

Enabled: false

# Shadowing outer local variables with block parameters is often useful

# to not reinvent a new name for the same thing, it highlights the relation

# between the outer variable and the parameter. The cases where it's actually

# confusing are rare, and usually bad for other reasons already, for example

# because the method is too long.

Lint/ShadowingOuterLocalVariable:

Enabled: false

# Check with yard instead.

Style/Documentation:

Enabled: false

# This is just silly. Calling the argument `other` in all cases makes no sense.

Naming/BinaryOperatorParameterName:

Enabled: falseNow, running Rubocop will only show 6 offenses, which isn’t that bad. I can see 3 different issues that I have to fix:

- Use

%i[]for symbol arrays. Using[:username, :email]is the same as%i[username email]. Notice the 2nd form doesn’t have colons and comas. - Use

find_byinstead ofwhere(…).first. Nothing wrong withwhere(…).first, just thatwhereis used to return multiple entries, andfind_byis used to return a single one. - Don’t use

binding.pry… at least don’t push it on a production server.

You might want to run rubocop automatically whenever you’re ready to commit code in git. Since git is expandable with hooks, you can use a pre-commit hook that won’t commit your code if there are offenses. This goes beyond the Rails’ scope, hence beyond the blogposts scope, so consider it a homework.

Creating the User Dashboard

Now that the users authentication is ready, we can start thinking of actually building features for the app. I’ll start by creating a dashboard (a stubby one), where the users will get redirected after they log in, where they’ll see (and later, create and update) their available slots. Also, I don’t want the landing page to be visible for logged-in users; there’s no reason for them to see that page.

Firstly, I’ll create a DashboardController with an index action, and the view returned is the view where we’ll build the dashboard:

# app/controllers/application_controller.rb

class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base

# ...

before_action :authenticate_user! # add this

protected

def after_sign_in_path_for(_) # add this

dashboard_path

end

# ...

end# app/controllers/dashboard_controller.rb

class DashboardController < ApplicationController

def index

end

end# app/views/dashboard/index.html.erb

<div class="valign-wrapper">

<h2 class="center-align">Welcome <%= current_user.username %></h2>

</div># config/routes.rb

get 'dashboard', to: 'dashboard#index' # add this

# app/controllers/pages_controller.rb

class PagesController < ApplicationController

skip_before_action :authenticate_user!, only: :hello

before_action :redirect_users, only: :hello

def hello

end

private

def redirect_users

return unless user_signed_in?

redirect_to dashboard_path

end

endWe’re using before_action :authenticate_user! on ApplicationController to make sure all the routes require an authenticated user. And we skip it for the landing page, since we don’t need users to be authenticated to see the landing page. We’re also using a before_action to redirect already logged in users from the landing page to the dashboard.

Spec a bit

This is one of those cases when I’m too lazy to write specs before writing the code (no TDD involved here), but I’m also too lazy to manually test what I’ve implemented. So what we’re doing now is no more TDD, just writing automated tests.

I want to write some tests on how the system behaves when the login credentials or the sign up parameters are wrong, and what happens when a logged in user tries to access the landing page, or a non-logged in user tries to access the dashboard. Since I’ve already implemented these, I expect the specs to pass (given they’re written correctly).

Before actually writing the specs, I want to configure a couple of things:

# Gemfile

group :development, :test do

gem 'ffaker', '~> 2.12' # add this

# ...

end

group :test do

gem 'factory_bot_rails', '~> 5.0', '>= 5.0.2' # add this

# ...

end

# CREATE THE FOLLOWING FILES

# spec/support/factory_bot.rb

RSpec.configure do |config|

config.include FactoryBot::Syntax::Methods

end

# spec/support/headless_chrome.rb

RSpec.configure do |config|

config.before(:each, type: :system) do

driven_by :selenium, using: :headless_chrome

end

end

# spec/support/devise_helpers.rb

RSpec.configure do |config|

config.include Devise::Test::IntegrationHelpers

end

# spec/factories/users.rb

FactoryBot.define do

factory :user do

username { FFaker::Lorem.words.join('') }

email { FFaker::Internet.email }

password { 'password' }

end

endWhat did we just do? We installed the FFaker gem to help us generate some fake test data, we installed and configured FactoryBot, we configured some Devise test helpers, and we configured a headless browser (chrome) to be used with the system specs. Now, for the real test, here’s how we test the login functionality (spec/system/login_spec.rb):

require 'rails_helper'

RSpec.describe 'Login' do

let(:user) { create :user }

before do

visit root_path

expect(body).to have_link('Log In')

end

context 'with valid params' do

let(:password) { 'password' }

it 'logs in with username' do

click_link 'Log In'

within(:css, 'form') do

fill_in 'Username or Email', with: user.username

fill_in 'Password', with: password

find('[type="submit"]').click

end

expect(page).to have_link('Log Out')

end

it 'logs in with email' do

click_link 'Log In'

within(:css, 'form') do

fill_in 'Username or Email', with: user.email

fill_in 'Password', with: password

find('[type="submit"]').click

end

expect(page).to have_link('Log Out')

end

end

context 'with invalid params' do

let(:password) { '12345678' }

it 'does not log in with username' do

click_link 'Log In'

within(:css, 'form') do

fill_in 'Username or Email', with: user.username

fill_in 'Password', with: password

find('[type="submit"]').click

end

expect(page).to have_text('Invalid Login or password')

end

it 'does not log in with email' do

click_link 'Log In'

within(:css, 'form') do

fill_in 'Username or Email', with: user.email

fill_in 'Password', with: password

find('[type="submit"]').click

end

expect(page).to have_text('Invalid Login or password')

end

end

endThis spec uses Capybara to emulate user behaviours. It’s clear that what we’re doing here, is describing what a typical user would do to login:

- Visit the root path (/)

- Click on the log in link in the navbar

- Fill the form with their username/email and password

- Click the Log in button

Finally, we expect to either see the logout button (if the login was done successfully), or an error message.

I added a couple of other spec files here, so check the diff.

Add a unique index for username

I just noticed that we don’t have an index for the username. This means that, when (if) our application gets thousands of users, searching through the database for a given username will take a while. Without indices, think of the database driver running a linear search for every record in the DB until it finds a matching username, or running out of entries. So, let’s do this:

$ rails g migration add_index_for_usernameclass AddIndexForUsername < ActiveRecord::Migration[6.0]

def change

add_index :users, :username, unique: true

end

end$ rails db:migrateTo sumarize

In this blogpost you saw Rails partials in action, configuring Devise for your needs, configuring Rubocop, stopping users from accessing views you don’t want them to access, and writing system specs. If you get into an already existing project, Devise and Rubocop will probably be already configured. Writing (system) specs is something that you’ll do more often than you think, so better get used to the syntax and to the toolset as soon as possible. As for Devise and its plethora of configurable options, the wiki covers almost everything you need.

All the code for this project is in this github repo. Next time, we’ll jump into creating the Slot model. See you then.

Previously posted on my Medium blog