During my Eurotrip this July, I visited a few cities around Central Europe. One of my destinations was Vienna and as any other boring tourist, I decided to take a stroll at the Schönbrunn Palace, Habsburgs’ summer residence. I will spare you the touristy mumbo jumbo and tell you about this nice little puzzle I found in their maze garden.

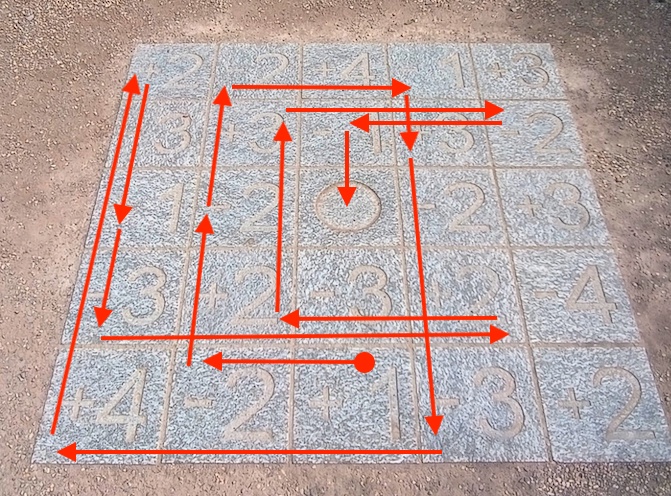

It’s a little math puzzle that looks like the pic you see above. And the rules are simple: you start at 1 — the middle tile of the bottom row — and you walk around the board as many cells as the number says (ignoring the sign), without stepping twice on a tile, until you reach the middle tile. That’s the easy version. The hard version is the same, but you also keep count of the sum of the tiles you’re stepping on (not ignoring the sign), and when you reach the middle tile your total should be zero.

I spent 2 minutes looking at it and came up with a solution, which is neither the solution of the easy version, nor that of the hard version. It looks like this, and I call it “The dumb solution”, because my German is broken and I didn’t quite understand what I was reading:

It is somewhat of a solution, the tiles on the path sum up to 0 and you still reach the center: 1 -3 +2 -4 +3 -2 +3 -1 +3 -2 = 0

But it’s not an actual solution to the puzzle. The puzzle requires you to jump more than

one tile: if the tile’s number is -2, you should walk 2 tiles up/down/left/right, and so on

until you find your way to the center. And if you find a dead end (which can happen

because you can’t step twice on the same tile), you should start back-tracking your steps

and follow a different path. Maybe it is not that obvious, but this 2D Array of numbers

is actually a graph, and this task children’s puzzle screams Depth-First Search.

So, I wrote a simple Go program to solve it because unlike Habsburgs, I didn’t fail my Algorithms and Data Structures course!

Go-ifying this puzzle

I will not bother with the graph representation of this, thinking in 2D arrays is easier:

puzzle := [][]int{

{2, -2, 4, -1, 3},

{-3, 3, 1, 3, -2},

{1, -2, 0, -2, -3},

{-3, 2, -3, 2, -4},

{4, -2, 1, -3, 2},

}But it’s also easier to not think of it as a 2D array of numbers. I have to think about cells, and visited cells, and cell coordinates in the puzzle, and it’s easer to think of the solution as an array of Cells (in the same order as you’d walk through them) and of the puzzle as a 2D array of Cells. So, instead of that, I’m doing something fancier:

type Coord struct {

Row int

Col int

}

type Cell struct {

Coord

Value int

Visited bool

}

func (cell *Cell) String() string {

var sign string

if cell.Visited {

sign = "*"

}

return fmt.Sprintf("(%d%s @ (%d, %d))", cell.Value, sign, cell.Row, cell.Col)

}

type Puzzle [][]Cell

func NewPuzzle(input [][]int) Puzzle {

cells := make([][]Cell, len(input))

for i, row := range input {

for j, _ := range row {

cell := Cell{

Value: row[j],

Coord: Coord{Row: i, Col: j},

}

cells[i] = append(cells[i], cell)

}

}

return Puzzle(cells)

}

// ...

func main() {

puzzle := NewPuzzle([][]int{

{2, -2, 4, -1, 3},

{-3, 3, 1, 3, -2},

{1, -2, 0, -2, -3},

{-3, 2, -3, 2, -4},

{4, -2, 1, -3, 2},

})

// ...

}

I made Cell implement the

Stringer interface, and also added a

func (puzzle Puzzle) CellAt(coords Coord) *Cell function to fetch the cell at

some given Coord. Nothing special so far.

Now, before jumping to finding the path. Given a cell, I want to get a list of possible

cells I can jump to. Thinking in graphs terms, I want to find which edges (Cells) are

connected to a given edge, and which of those edges isn’t already visited.

If I’m stepping on cell {0, 2} for example (middle of first row),

I am only allowed to go to cell {4, 2}.

This because the cell on {0, 2} has the value 4, and jumping 4 cells up/left/right will

throw me away of the puzzle, and that particular area of the floor is lava…

func abs(x int) int {

if x < 0 {

return -x

}

return x

}

func (puzzle Puzzle) UnvisitedNeighborsForCell(cell *Cell) []*Cell {

var neighbors []*Cell

cellValue := abs(cell.Value)

maybeCoords := []Coord{

Coord{Row: cell.Coord.Row - cellValue, Col: cell.Coord.Col},

Coord{Row: cell.Coord.Row + cellValue, Col: cell.Coord.Col},

Coord{Row: cell.Coord.Row, Col: cell.Coord.Col - cellValue},

Coord{Row: cell.Coord.Row, Col: cell.Coord.Col + cellValue},

}

for _, coords := range maybeCoords {

if coords.Row < 0 || coords.Row >= len(puzzle) {

continue

}

if coords.Col < 0 || coords.Col >= len(puzzle[coords.Row]) {

continue

}

if puzzle.CellAt(coords).Visited {

continue

}

neighbors = append(neighbors, puzzle.CellAt(coords))

}

return neighbors

}It’s straightforward as finding which of the potential maybeCoords are inside

the non-lava part of the world, and which of them is not already visited. And with

all these tools in hand, we can jump head-first into the depth-first search:

func (puzzle *Puzzle) FindPath(from, to *Cell) (bool, []*Cell) {

path := []*Cell{from}

from.Visited = true // mark as visited

if from == to { // found the target

return true, path

}

nextCells := puzzle.UnvisitedNeighborsForCell(from)

for _, nextCell := range nextCells {

nextCell.Visited = true

found, restOfPath := puzzle.FindPath(nextCell, to)

if found {

path = append(path, restOfPath...)

return true, path

}

if restOfPath == nil { // backtrack

nextCell.Visited = false // reset visited flag

} else {

path = append(path, restOfPath...)

}

path = path[:len(path)-1]

}

return false, path

}If you want a primer on DFS, I’m not sure I can explain it better and more thoroughly than Reducible, so head there and learn some more about it. Either way, take my word for it. This search here is very depth-first-y.

The general gist is that the algorithm of

finding the path starts at a cell named from and tries to find a cell named to.

If, by any chance, these “two cells” are the same, the whole path is solved:

you’re already there.

Otherwise, the algorithm tries to recursively find the path to to from one of from’s

neighbors, marking each cell on its way as visited so we don’t step twice on them.

If nothing is found and the algorithm reaches a dead-end on one of its recursive calls,

it marks the cell as unvisited (because we simply visited it by mistake), backtracks

its steps and tries with a different path.

In essence, this algorithm explores the puzzle by moving from cell to cell,

marking them as visited as it goes. It tries different paths and backtracks

when it reaches dead ends until it finds a path from from to to, or

determines that no such path exists.

Wiring everything together

func main() {

puzzle := NewPuzzle([][]int{

{2, -2, 4, -1, 3},

{-3, 3, 1, 3, -2},

{1, -2, 0, -2, -3},

{-3, 2, -3, 2, -4},

{4, -2, 1, -3, 2},

})

beginning := puzzle.CellAt(Coord{4, 2})

ending := puzzle.CellAt(Coord{2, 2})

_, path := puzzle.FindPath(beginning, ending)

printSolution(path)

}

func printSolution(solution []*Cell) {

for _, cell := range solution {

fmt.Printf("%v -> ", cell)

}

fmt.Println()

}And the solution to the Schönbrunn Palace is:

(1* @ {4, 2}) -> (-2* @ {4, 1}) -> (-2* @ {2, 1}) -> (-2* @ {0, 1}) ->

(-1* @ {0, 3}) -> (3* @ {1, 3}) -> (-3* @ {4, 3}) -> (4* @ {4, 0}) ->

(2* @ {0, 0}) -> (1* @ {2, 0}) -> (-3* @ {3, 0}) -> (2* @ {3, 3}) ->

(2* @ {3, 1}) -> (3* @ {1, 1}) -> (-2* @ {1, 4}) -> (1* @ {1, 2}) ->

(0* @ {2, 2}) ->

In just 17 steps, you can go from that 1 cell at {4, 2} to that 0 cell at {2, 2}! And you can find the full source code (a single file) in this Gist.